Evolutionary pressures shaped the psychology of human beings—along with every living creature on Earth. These pressures created an abundance of impactful genetic differences in humans, which explain substantial portions of all human behaviors—a fact so well-replicated it is considered the first law of behavioral genetics. Since genes influence behavior and behavior creates society, the role of genes is relevant to almost every major issue of politics, economics, and culture. The commonly-held ideological commitment to “blank slatism” among Western intellectuals has led to a failure to consider genes as an important causal variable in the most important questions concerning humanity, severely undermining the explanatory power of the social sciences.

While many conservatives reject the role of evolution in human behavior on religious grounds, progressives often reject it largely on account of a moral commitment to human equality. While practically all progressives acknowledge the reality of Darwinian evolution, few seriously consider the implication that human behavior would be genetically influenced and that there would be variation that produces social and economic inequalities. Such a belief has been dismissed as genetic determinism and essentialism. The favored explanation among progressives is that socioeconomic differences are the product of the unjust treatment of marginalized people by the oppressor groups.

While progressivism is well characterized by a strong emphasis on the moral foundations of harm avoidance and equality, progressive thinking rests on a huge number of causal claims. Unlike conservative explanations for human behavior, progressive theories carry much more weight among intellectuals and academics. Progressives tend to believe ideas such as (1) better-funded education can equalize academic outcomes, (2) socioeconomic status strongly determines life outcomes, (3) disparities in outcomes are largely attributable to discrimination, and (4) wealth is mostly the result of privilege and luck. Causal claims such as these motivate policy recommendations. For example, a belief in the importance of well-funded education motivates calls for more spending.

These positions are typically rejected by hereditarians—believers in the importance of genes—who are overwhelmingly more common on the right. This position is not forwarded by many mainstream conservative intellectuals and is much more commonly found online among what has been termed the dissident right. One common objection from progressives toward this idea is that it is supported by people who have what they see as repugnant moral beliefs (e.g., opposition to affirmative action, immigration, and sometimes explicit advocacy for the interests of what have been regarded as privileged groups).

There is a sizeable number of hereditarian progressives who fail to see the good in publicly promoting the importance of genes, believing that it will contribute to the resurgence of unsavory attitudes such as classism, racism, sexism, and eugenicism. There is a reasonable concern that lifting the taboo on genetic determinism could result in regression to an anti-egalitarian society that ceases to care about uplifting the less fortunate. Many progressives are afraid to discuss such topics because they are afraid of being regarded as someone with unethical moral views. This has contributed to the strong inverse relationship between hereditarianism and progressive moral commitments. Few progressives openly embrace genes as an explanation for individual and sex differences and virtually none do so for other group differences (e.g., national, ethnic, religious).

While stronger forms of hereditarianism undermine many of the typical progressive causal explanations—and thus social interventions—it is still possible to believe in the virtue of egalitarianism. Progressives already recognize that society can be difficult for the congenitally less able-bodied. These sorts of disparities are recognized as cosmic injustices—outside of anyone's control—but the fact that they are not the product of interpersonal injustices does not lead progressives to reject them as an unworthy cause. Many progressives—and conservatives—advocate for accommodation, empathy, and social assistance for the less able-bodied. A move toward progressive hereditarianism calls for a reinterpretation of many interpersonal injustices as cosmic injustices.

The benefit of embracing true explanations for human behavior is that they allow us to discover and implement policies that are actually effective. Social interventions premised on false causal explanations will not produce desirable outcomes. They will fail, resulting in potentially unwanted harm and wasting resources that could be spent on effective interventions. Potential true environmental contributions are possibly obfuscated when investigations fail to account for potential genetic confounding. Studies that account for known sources of confounding are likely to be more fruitful, as they will more frequently identify environmental influences that reflect true causal relationships. Schmidt (2017) describes one example of the problem of unconsidered confounding:

Several studies reported that children who are exposed to the classical music of Mozart have higher IQs (Campbell, 2001; Hetland, 2000). The implication is that the music caused the higher IQs. There is no mention in these studies of the possibility that parental general mental ability (GMA) and socioeconomic status (SES) are the real causes. Classical music is more often played in higher SES homes and parental GMA levels are higher on average in such homes. And GMA is highly heritable (about .75 in adulthood; Bouchard, 1997b; heritability varies somewhat by social class, and is higher than .75 in the elderly). When experimental studies were conducted that controlled for this, the Mozart Effect was found to be nonexistent (Steele, Bass, & Crook, 1999). Nevertheless, these reports led Governor Zell Miller of Georgia to arrange for all families with children in that state to receive a CD of Mozart’s music and other classical music (History.com, 2010; Mackenzie, 1999).

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of the rejection of genetic influence is its association with the rejection of advancing genetic enhancement—which is attacked as a resurgence of eugenics, despite the fact that it does not share the immoral aspects of its past implementation—coercion and harm. Reprogenetic technology like polygenic embryo screening actually gives more control to the parent and facilitates better-informed reproductive decisions that produce children that live better lives.

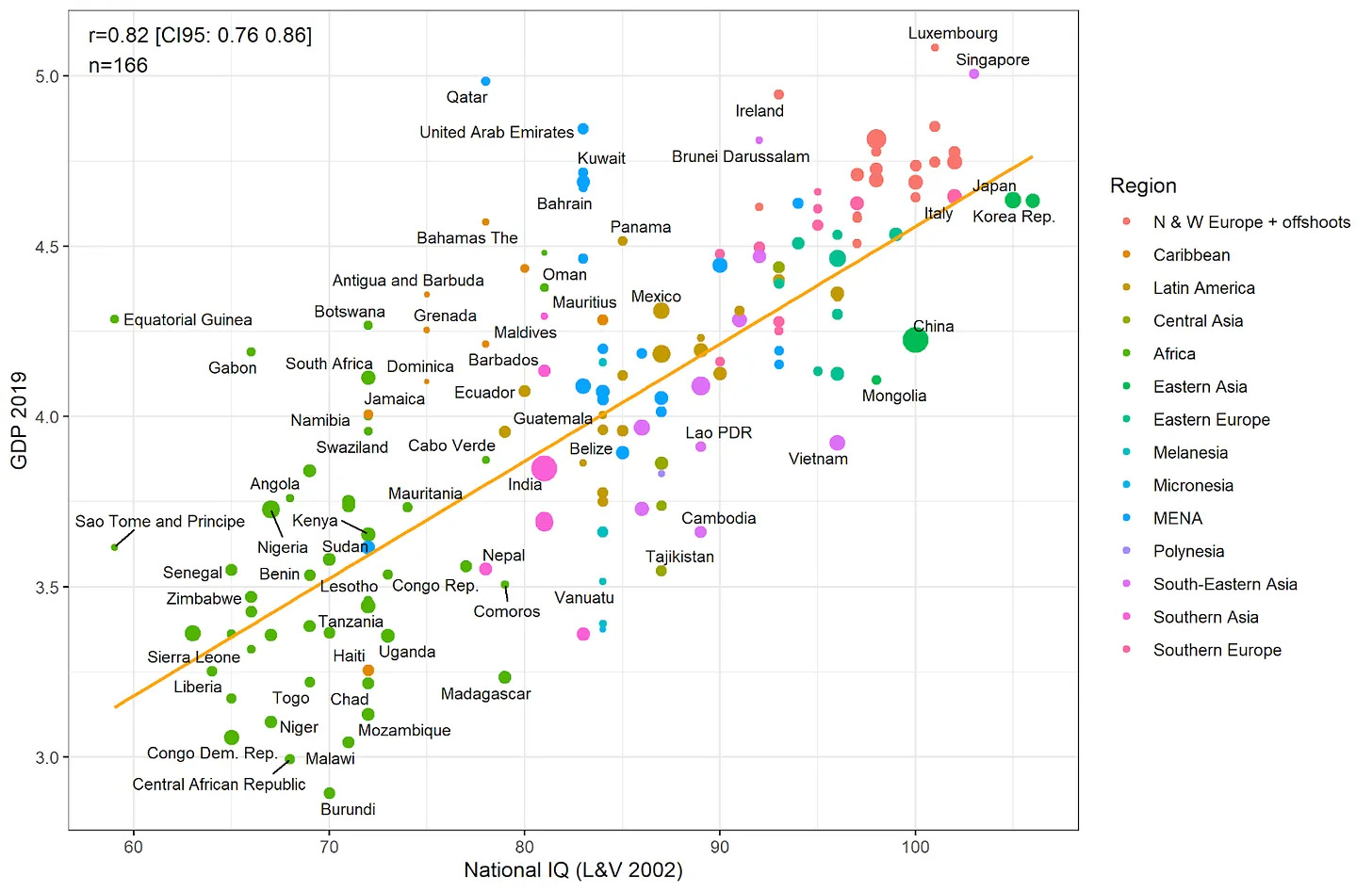

The public hesitancy toward genetic enhancement is especially troubling because the potential for good is so large. Every trait for which siblings show differences is subject to selection using polygenic embryo screening, and in the near-future we may have the capability to either select from extremely large batches of embryos or precisely edit genes. The expected returns from such technology will be much larger than any available environmental interventions. Selection for traits like cognitive ability as measured by IQ could contribute to reducing poverty and accelerating technological growth. Our future descendants could be living lives that are much longer, healthier, happier, and more prosperous.

One of the major concerns among progressives is that genetic enhancement technology could actually exacerbate inequality. Since there are positive network effects to traits like intelligence, the returns will be largely distributed across society uplifting even the less fortunate. Still, a disproportionate amount of the benefit would go to the genetically enhanced population. For that reason, we should go further. In addition to accelerating research into this technology, we should be advocating for universal subsidy of the use of this technology so the benefits can go to the less fortunate members of society.

Such a proposal may be disconcerting for many. They may be worried that we are choosing genetic enhancement over social interventions. In reality, there is no reason why we cannot have both. We should continue identifying societal injustices and potential areas of concern where they are present, but we need to take a more rigorous approach to research in order to consider potential genetic differences in order to identify effective interventions. If we discover an intervention is not worthwhile, we should stop pursuing it. In such cases, it would be better to simply redistribute the money to the less fortunate. We can still pursue environmental interventions while investing heavily in genetic enhancement technology.

Some may still have a lurking concern about a rise in unsavory political ideologies. That is understandable, but rather than claiming these empirical beliefs are inextricably linked to moral beliefs, we should reiterate that nothing heinous follows from a belief in the importance of genes. We can maintain a progressive belief in the virtues of uplifting the less fortunate and promoting equality while simultaneously acknowledging certain realities about the plausibility of certain approaches to achieving this goal.

If we continue to live in an open society that allows scientific research, evidence will accumulate to support whatever facts are actually true about the role of genes in society. The cost of sequencing has been rapidly falling for the past two decades, and the size of genomic databases is ever-increasing. Many questions regarding the human genome will be answered in the coming years. If the hereditarian perspective is wrong, we should want to accelerate the genomic research to debunk it. If it is right and someday it will be necessary to face that fact, progressives should not let the right have a complete dominance of the discussion when that day comes. Adherents to any ethical belief—whether it be progressivism or otherwise—will be more effective if they embrace the truth. I call this vision for a new progressivism compassionate biorealism.

My personal thesis is the US is probably doomed - it has enough people on both sides of the political aisle that are against genetic explanations and *definitely* against gengineering, that it's extremely unlikely to adopt broad-scale gengineering fast enough to compete with countries like Russia or China that will embrace it wholeheartedly.

I've always assumed I'd need to travel to Estonia or Thailand or Singapore (or maybe somewhere like Prospera) to get my kids gengineered. If I have to give up US citizenship to do it (which seems a fairly likely reactive bipartisan Schelling point to gengineering existing for the rich and being actually effective), I'll do that happily and with zero hesitation.

I mean, the problem is that aside from gengineering, "you can't fix stupid." Well, what if "stupid" outlaws gengineering? Whichever countries do that are going to lose on a massive economic and human capital scale over the next few decades.

Wonderful article! My view is basically compassionate or beneficentrist libertarian capitalism. https://rychappell.substack.com/p/beneficentrism

God bless all of us!